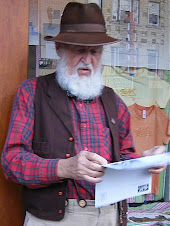

There is an idea of the Southwest that lives in the collective mind. It is embodied through stoic figures that represent unsympathetic landscapes where little is spoken. Poet and songwriter Kell Robertson was drawn to the Southwest by idealized images of the black-and-white films of his youth. His poems—published in more than 13 books—speak like the ghosts of another time.

Don’t call Kell Robertson a beatnik, just call him a writer. |

In his poem “The Old Man Goes Home,” Robertson writes, “All I can see is what we’ve lost.”

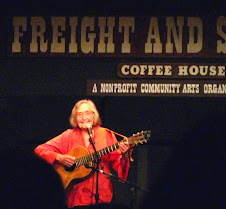

It is this sense of longing for his childhood home in Elk City, Kan., that informs the memory of his friend Utah Phillips. Phillips was an enigmatic singer-songwriter, poet and labor organizer cast from Woody Guthrie’s America. Phillips, who died earlier this year, harbored no avarice, no reason to be something he wasn’t. It is an attribute that endeared him to other artists such as Tom Waits and Ani DiFranco, who would eventually cut two records with Phillips, one of which, Fellow Workers, earned a Grammy nomination.

Robertson headlines a celebratory event in memory of Phillips and his friendship. It is a fitting tribute filled with poetry, music and memories.

SFR: How did you first come to poetry?

KR: Probably with Percy Bysshe Shelley. My mother was an avid reader. By the time I went to school—at around the age of 8—I had read Shakespeare. I was lucky. She had the works of Shakespeare and the complete works of Zane Grey, so I had that influence.

That’s quite a reach from Shakespeare to Zane Grey.

Well, yeah…sorta…kinda, maybe, in a way. I went into the military and I got out of it because I hated it; I hated war. I hated the whole thing, so I grabbed my guitar and headed to Mexico and hung out here for a while and eventually hitchhiked across America. Writing became such a natural thing to me. I’ve read all the poets. I know all the stuff. I’ve read all the critics and all the academic jerks.

You’ve been called a beat poet. What do you think about that classification?

Well, you know, it’s very funny. On one of my books Lawrence Ferlinghetti wrote a blurb, ‘Kell is one fine cowboy poet.’ I’ve been called a beat poet, a

KELL ROBERTSON WITH JOE WEST, KENDALL MCCOOK, MITCH RAYES, RICHARD MALCOLM, GEORGIE ANGEL AND PATRICK HOULIHAN 7 pm Monday, July 14 $5 Santa Fe Brewing Company 35 Fire Place 424-9637 |

How did you meet Utah Phillips?

I met Utah in San Francisco years ago with Rosalie Sorrels, his singing partner at the time. He’s a reformed alcoholic, and I’m a perpetual drunk. The two of us walked around each other over the years. He would run into me and say, ‘Hey Kell, you still drinking?’

Utah never diverted from who he was…

No, he was a Wobbly all the way. He clung to those old ideas and I agree with him. He told stories better than anyone I’ve ever seen. He would talk about the old days with the Wobblies, the labor unions, traveling on box cars, about living as a hobo, fighting the cops. It was a time and a place that really happened. He could get really into what he did, which was talking about working people and being poor in America. He was the genuine thing.

You’ve lived in a lot places. Have those regions influenced your writing?

I grew up with poor people. I have an eighth-grade education, that’s it. The rest of it I got on my own, self-taught all the way. I love this country. I’m in the Southwest because I like the people and I love Mexican music. My mother took me to see Hank Williams [Sr.] in Shreveport, La. He dropped the microphone; he was drunk and he just blew everybody away. I looked at him and said, ‘I want to do that.’ And then I heard Dylan Thomas read and I said, ‘I want to do that.’

You think that kind of experience can still be had with young people, with poetry?

I don’t know; I worry about it. I don’t know if it’s possible at all. There’s about a million slam poets and poetry drill teams…I’m not sure if that does it any good. I think it’s something that you have to uncover on your own.

William Faulkner once said about his work, ‘I’m just a farmer who likes to tell stories.’ I’ve read some of your poems and I’m curious if you think people tend to over-think or overanalyze them.

Those stories in the songs and the poems are personal. I did most of those things or at least I knew people who did. Of course, in the back of your head, if you have a sense of language and understand rhetoric, line, meter and all that crap…the poem or the song just comes to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment